Theater LaB Houston introduced a new park for City of Houston…

THESPIAN PARK

Opened on Sunday April 27, 2003

Located minutes from the heart of downtown in one of Houston’s oldest neighborhoods – the historic First Ward – Theater LaB Houston presents its most exciting and dynamic production to date – Thespian Park. From the Romans and Greeks to the modern Broadway stage, internationally renowned Rodolphe Zarka has designed and brought to life on mural panels an epic history of theater through the ages. With his sweeping and bold brush strokes that will delight the eye, unique and eclectic placement of symbols that will challenge the mind, Zarka’s mural panels at Thespian Park will stand as a lasting curtain call to the achievements of theater.

An artistic journey that includes Kabuki, Shakespeare, French, Italian, Latin American

and more of the ages of theatrical accomplishments, this visual park is a

welcome addition to Houston’s dramatic arts scene for its citizens and visitors.

Further visual pleasure is provided by the whimsical

color gardens that flow beneath the murals, graciously maintained and donated

through unwaving support and friendship to Gerald by Kathleen Gay Peeples.

The major undertaking of the creation of Thespian Park has been completed.

Located across the street from Theater LaB, this 6500 square foot parcel of property

was purchased by the theater to create a unique landscape corner with murals to enhance

the revitalization and redevelopment of the First Ward.

The park provided a green space for theater patrons to visit before and during intermissions of Theater LaB productions. Internationally renowned artist Rudy Zarka was commissioned to create the murals. His concept included a mural of individual panels tracing the history of theater through the ages. Zarka has several major murals in Houston as well as international locations.

His previous work for the theater includes set design and mural work on the productions

of subUrbia and the award-winning design of Avenue X, the a cappella musical.

Thespian Park closed and was disassembled in December 2012

Kathleen Gay Peeples

About the Artist Rodolphe N. Zarka

When Thespian Park was conceived not only as a green space, but also the site of fantastic murals

depicting the history of theater, the choice of the artist was obvious – Rodolphe N. Zarka.

Born in France, Zarka was an artist of wide range and imagnative vision.

His mastery of visual with the conceptual understanding of theory has resulted in the production of murals, set designs, and structural designs. In Houston, several of Zarka’s murals are on display: The Carnival in Venice at Baffoni’s Restaurant, Revival of Mayan Frescos of Bonapak at Palazio Tzintzuntzan, Homage to Miro at LaGriglia and numerous private commissions. His eye for beauty and truth in conjunction with the practicalities required and the understanding of theater, has served in set designs for such work as Goha the Simple with Omar Sharif, a collaborative creation for Lawrence of Arabia, and in Houston: suburbia and Avenue X for Theater LaB Houston. He was awarded Best Set Design by The Houston Press for his work at Theater LaB Houston. Other achievements include the Grand Prix of Architecture from the City of Tunisia, French Delegate to the International Congress of Architects in Stockholm, and the Economic Mission for the Belgian Government to the U.S. and Canada.

A master of form, Zarka has brought his astute detail and enormous range of knowledge to Thespian Park. The vast and time-spanning murals commissioned by Theater LaB Houston enable us to step into the world, language and images of theater. Zarka took the concept of theater history and boldly ran with it – shaping it beyond his personal vision to be a vision for all of us, giving us a visual panorama of the enormity and the impact of theater through the ages.

When Thespian Park was conceived not only as a green space, but also the site of fantastic murals

depicting the history of theater, the choice of the artist was obvious – Rodolphe N. Zarka.

Born in France, Zarka was an artist of wide range and imagnative vision.

His mastery of visual with the conceptual understanding of theory has resulted in the production of murals, set designs, and structural designs. In Houston, several of Zarka’s murals are on display: The Carnival in Venice at Baffoni’s Restaurant, Revival of Mayan Frescos of Bonapak at Palazio Tzintzuntzan, Homage to Miro at LaGriglia and numerous private commissions. His eye for beauty and truth in conjunction with the practicalities required and the understanding of theater, has served in set designs for such work as Goha the Simple with Omar Sharif, a collaborative creation for Lawrence of Arabia, and in Houston: suburbia and Avenue X for Theater LaB Houston. He was awarded Best Set Design by The Houston Press for his work at Theater LaB Houston. Other achievements include the Grand Prix of Architecture from the City of Tunisia, French Delegate to the International Congress of Architects in Stockholm, and the Economic Mission for the Belgian Government to the U.S. and Canada.

A master of form, Zarka has brought his astute detail and enormous range of knowledge to Thespian Park. The vast and time-spanning murals commissioned by Theater LaB Houston enable us to step into the world, language and images of theater. Zarka took the concept of theater history and boldly ran with it – shaping it beyond his personal vision to be a vision for all of us, giving us a visual panorama of the enormity and the impact of theater through the ages.

T H E P A N E L S

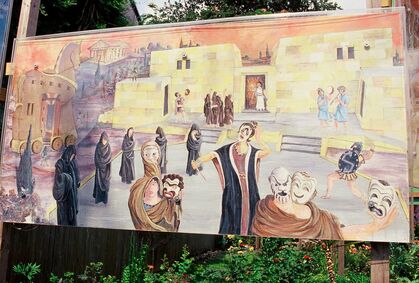

The Greeks

The Greeks invented tragedy. Aristotle believed that tragedy grew and evolved form the improvisations by leaders of dithyrambs – hymns sung and danced in honor of Dionysus, son of Zeus, and the Greek god of wine and fertility. The word tragedy literally means goat-song – probably taken from the ceremony of taking a goat as a prize or sacrifice. In 534 B.C., the Athenian government gave official sanction and financial support to theater with a contest for the Best Tragedy presented in the City of Dionysia. With their belief in human rationality and acknowledgement of unpredictability, the Greeks used the forum of theater to explore the human condition, including suffering. Derived from variations on the Aegean civilization’s gods, heroes, and history, by the late 4th Century B.C., drama was the most prized form of literature, and theater, the most popular art form.

The first great era of theater is considered to be between the 8th and 6th Centuries B.C.

The woes of Classical Greece are portrayed in the mural paying homage to Greek Theater, incorporating general and specific references. The setting is the Theater of Dionysia. Here we find Medea and the Trojan Horse, as well as recurring features of Greek theater – the lamenting women, masks that suggest the multiple faces of actors in happy, sad, evil and good roles, musicians, and the Greek Chorus. In the doorway id the king bearing the head of his enemy and downstage is the assassin, a recurring motif in Greek Theater. In the background is the Parthenon.

This is the foundation on which modern drama continued to be built.

Theater of Dionysia – completed late 4th Century B.C.

Medea – Euripides, 480-406 B.C., wrote 90 plays

The Trojan Horse – Homer, 8th Century B.C.

The Greek Chorus – functioned as a character in the Greek dramas with the purpose of establishing the framework for the action,

serving as ideal spectator, setting the mood, adding spectacle, and providing rhythm..

The first great era of theater is considered to be between the 8th and 6th Centuries B.C.

The woes of Classical Greece are portrayed in the mural paying homage to Greek Theater, incorporating general and specific references. The setting is the Theater of Dionysia. Here we find Medea and the Trojan Horse, as well as recurring features of Greek theater – the lamenting women, masks that suggest the multiple faces of actors in happy, sad, evil and good roles, musicians, and the Greek Chorus. In the doorway id the king bearing the head of his enemy and downstage is the assassin, a recurring motif in Greek Theater. In the background is the Parthenon.

This is the foundation on which modern drama continued to be built.

Theater of Dionysia – completed late 4th Century B.C.

Medea – Euripides, 480-406 B.C., wrote 90 plays

The Trojan Horse – Homer, 8th Century B.C.

The Greek Chorus – functioned as a character in the Greek dramas with the purpose of establishing the framework for the action,

serving as ideal spectator, setting the mood, adding spectacle, and providing rhythm..

The Romans

The mural depicts The Gladiators in the Roman Colosseum, initially known as The Flavian Amphitheatre. Originally three stories tall

(a fourth was added in the third century AD), the amphitheatre was an architectural marvel: 157’ tall, 620’ long, 513’ wide.

The time is sometime between 80 BC, when the Colosseum was completed and 1 A.D.. This is the theater of politics.

Before 50,000 spectators, specially designed elevators brought scenery, wild beasts and combatants from subterranean floors

to the arena level. The actors in these particular dramas were real, the fight was real, the ending was final.

Someone would live. Someone would die. Royalty often decided the plight of the actors, the warriors. Who should live and who should die?

The audience voted. The Court had the final say. While stigmatized in Roman society, literature, and legislation, the gladiator events

were heavily attended and glorified. Was this barbarian cruelty inconsistent with or central to Roman civilization?

Were the deaths of humans and animals symbolic of the defense of civilization and social order, pushing the limits of morality and law?

Historians and critics still debate. On the right hand side of the painting sits the court reigning over the events.

The spectators have gathered to view the stage of blood, violence, defeat, triumph. The fighters use nets and weapons

as the props of battle. In cages surrounding the stage, beasts are held awaiting their entrance cues. The theatrics of the

Roman Gladiators cannot be denied. People have always gathered to see a show. This show consisted of bloodshed, of mortality.

The drama was obvious. The fear was passionate. The heroics not imagined. This historic theatre paved the way for our

eternal fascination with blood lust. As we observe this frozen moment, we must question our current motives, our current morality,

our still reigning lust for violence in art. We must consider our society¹s entertainment.

Have we come so far?

(a fourth was added in the third century AD), the amphitheatre was an architectural marvel: 157’ tall, 620’ long, 513’ wide.

The time is sometime between 80 BC, when the Colosseum was completed and 1 A.D.. This is the theater of politics.

Before 50,000 spectators, specially designed elevators brought scenery, wild beasts and combatants from subterranean floors

to the arena level. The actors in these particular dramas were real, the fight was real, the ending was final.

Someone would live. Someone would die. Royalty often decided the plight of the actors, the warriors. Who should live and who should die?

The audience voted. The Court had the final say. While stigmatized in Roman society, literature, and legislation, the gladiator events

were heavily attended and glorified. Was this barbarian cruelty inconsistent with or central to Roman civilization?

Were the deaths of humans and animals symbolic of the defense of civilization and social order, pushing the limits of morality and law?

Historians and critics still debate. On the right hand side of the painting sits the court reigning over the events.

The spectators have gathered to view the stage of blood, violence, defeat, triumph. The fighters use nets and weapons

as the props of battle. In cages surrounding the stage, beasts are held awaiting their entrance cues. The theatrics of the

Roman Gladiators cannot be denied. People have always gathered to see a show. This show consisted of bloodshed, of mortality.

The drama was obvious. The fear was passionate. The heroics not imagined. This historic theatre paved the way for our

eternal fascination with blood lust. As we observe this frozen moment, we must question our current motives, our current morality,

our still reigning lust for violence in art. We must consider our society¹s entertainment.

Have we come so far?

Medieval – The Traveling Chameleons

2007The time is the Middle Ages, approximately 500-600 A.D. The Western Roman Empire has crumbled and the state can no longer finance theater performances. The once popular mime troupes have disbanded. Actors have become outcasts, devil children, denounced by the church.

Theatre still finds a way to survive. Small nomadic bands of performers journey the countryside in search of an audience.

They are storytellers, jesters, tumblers, jugglers, musicians, troubadours, and animal trainers. They parade from castle to castle seeking

to be allowed in for a meal and a night¹s shelter in exchange for performance. Each castle had its own priest, so the stories

these traveling performers told of love between men and women would include God and would therefore pass the scrutiny of the Church.

While not formal dramatic pieces, their sketches included stories of death and the afterlife - Morality plays. In this mural,

the troupe is leaving town, taking their band of merriment on to the next. A stunning and whimsical sight, full of color and noise,

wearing the costumes and the masks of animals, they travel across the countryside led by the image of death from

Ingmar Bergman¹s classic film The Seventh Seal, from which the second row of troubadour images was also taken.

Ingmar Bergman – 1918-2007

The Seventh Seal—1956

Theatre still finds a way to survive. Small nomadic bands of performers journey the countryside in search of an audience.

They are storytellers, jesters, tumblers, jugglers, musicians, troubadours, and animal trainers. They parade from castle to castle seeking

to be allowed in for a meal and a night¹s shelter in exchange for performance. Each castle had its own priest, so the stories

these traveling performers told of love between men and women would include God and would therefore pass the scrutiny of the Church.

While not formal dramatic pieces, their sketches included stories of death and the afterlife - Morality plays. In this mural,

the troupe is leaving town, taking their band of merriment on to the next. A stunning and whimsical sight, full of color and noise,

wearing the costumes and the masks of animals, they travel across the countryside led by the image of death from

Ingmar Bergman¹s classic film The Seventh Seal, from which the second row of troubadour images was also taken.

Ingmar Bergman – 1918-2007

The Seventh Seal—1956

The New World

Before the Spanish combined morality and cyclic plays to create the theatre of auto sarramentales, there was ritual.

In 1550-1765, auto sacramentales linked with the festival of Corpus Christi emphasized

the power of church sacraments.The plays mingled human, supernatural, and allegorical characters

providing religious teaching, as well as mass entertainment.

The same basic process holds true in the theatre of life--dramatic undertakings that are

threaded into the everyday and the religious, from Paganism to Catholicism.

The glory and color of Latin Ritual and Celebration is presented here as primitive theater.

What is theater if not an event, a gathering of heightened emotions, a spectacle of music, the beauty of dance,

the display of multi-colored costumes? On the upper left atop the pyramid is a Mayan sacrifice. Traveling across the top width

are figures representing Mayan deities, such as the Sun God. The right side of the canvas is the Feast of Fire.

the lower mid left area are mariachis, modern Mexican musicians.

The lower left side depicts Los Dios de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead.

In 1550-1765, auto sacramentales linked with the festival of Corpus Christi emphasized

the power of church sacraments.The plays mingled human, supernatural, and allegorical characters

providing religious teaching, as well as mass entertainment.

The same basic process holds true in the theatre of life--dramatic undertakings that are

threaded into the everyday and the religious, from Paganism to Catholicism.

The glory and color of Latin Ritual and Celebration is presented here as primitive theater.

What is theater if not an event, a gathering of heightened emotions, a spectacle of music, the beauty of dance,

the display of multi-colored costumes? On the upper left atop the pyramid is a Mayan sacrifice. Traveling across the top width

are figures representing Mayan deities, such as the Sun God. The right side of the canvas is the Feast of Fire.

the lower mid left area are mariachis, modern Mexican musicians.

The lower left side depicts Los Dios de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead.

Kabuki

Set at sunrise on a traditional Japanese Noh stage, which has been standardized since 1615, this mural draws us

into the world of Kabuki. Initiated in 1603 by a female dancer, Kabuki borrowed freely from both Noh,

the first great Japanese theatrical form which emerged in the late 14th Century, and puppetry.

Melodramas in spirit, Kabuki drama is not literature, and there are no firm boundaries between comedy and drama.

It is performance, sometimes lasting as much as ten hours or more, that evokes a state or mood with

a series of loosely connected episodes focusing on climax, rather than plot, and culminating with dance.

The tales include supernatural ghosts and demons, domestic intrigue, and historical tales.

Traditional Japanese symbols, such as the almond tree and black bird, and characters are presented

in this representation of Kabuki. Heavily made up actors wear the costume required for the role portrayed:

the bad guy, good guy, the abused woman, the jealous husband, the lover, the warrior.

These are some of the recurring roles performed by the speaking/singing actors

that create what remains the most popular theatrical form in Japan.

into the world of Kabuki. Initiated in 1603 by a female dancer, Kabuki borrowed freely from both Noh,

the first great Japanese theatrical form which emerged in the late 14th Century, and puppetry.

Melodramas in spirit, Kabuki drama is not literature, and there are no firm boundaries between comedy and drama.

It is performance, sometimes lasting as much as ten hours or more, that evokes a state or mood with

a series of loosely connected episodes focusing on climax, rather than plot, and culminating with dance.

The tales include supernatural ghosts and demons, domestic intrigue, and historical tales.

Traditional Japanese symbols, such as the almond tree and black bird, and characters are presented

in this representation of Kabuki. Heavily made up actors wear the costume required for the role portrayed:

the bad guy, good guy, the abused woman, the jealous husband, the lover, the warrior.

These are some of the recurring roles performed by the speaking/singing actors

that create what remains the most popular theatrical form in Japan.

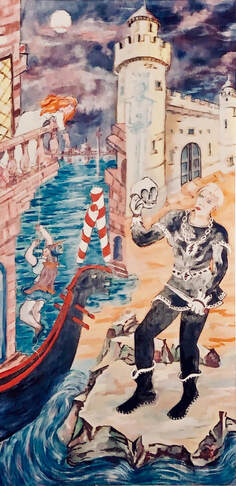

The Commedia dell'Arte

Travel to Venice between 1570 -1650. On an improvised set out of doors, we find a professional troupe of actors. Included are Capitano, braggart lover in rich costume; Pantalone, the merchant; Dottore, his friend or rival; Harlequin-- a zanni or servant, an acrobat, dancer, a mixture of cunning and stupidity found at the center of the play¹s intrigue; Pulcinello, the hunchback; Pierot, the dreamer; as well as a bird man, monkeys, bears, a little dog. These are the stock players of Commedia dell’arte that began to form in Italy perhaps as early as 1545, but was well established by 1568. The theatrical form remained the most typical and popular entertainment well into the 18th century. Writer/Actor Angelo Beolco, tired of Italian farce, inspired by the everyday life and simple speech patterns of Northern Italy, began writing plays with stock characters that became the forerunners for Commedia dell’arte. Mostly comic, though sometimes serious and often melodramatic, the professional troupe worked with a plot outline and improvised the rest. Stock characters varied slightly from troupe to troupe, but remained consistent within the troupe with each player always portraying the same character with the same attributes and costuming. Whether the performance was on a court stage or a hastily created outdoor stage, audiences watched the players become familiar characters--some straight and dignified, some overblown, exaggerated and fantastic, and all with the impression of spontaneity, spinning tales of love, intrigue, disguises, and cross-purposes. The dialog and action was fresh with each viewing, with bits of popular culture¹s literature and poetry carefully interspersed to delight and amuse. Zarka has chosen three colors to create his scene--red, black and grey. In the 17th Century, paints were created using the dyes of plants, and the choices were thus limited to be cost efficient. The strong use of red brings out the spirit of Commedia dell’arte--the whimsy and the mischief--drawing us in, capturing our imaginations, inviting us to play along.

The French Classics

On the forefront of the canvas you see the Court--the King, Queen, Bishop, their guests. They are dining on the stage as they enjoy the performance before them. To the left are the aristocrats in the balconies. Further away, out of your spectator¹s view, are the commoners--talking, fighting, insulting the actors, out for a good evening of entertainment. This is the Theatre of the King: Theatre du Roi. It is the 18th Century, a time of political movement and unrest. As people begin to think politically, the defense of humanity is verbally reflected in the work on stage. Paris dominates the world of theatre and culture and sets the standard of drama by which all others will be judged. Gracing the stage will be a play of manners and social customs, probably a comedy by Moliere, the grey figure to the left, who dominated French comedy until 1720. The performance will be one of complex plot and relationships and unveilings. The action will take place in a twenty-four hour time span. The court will be mocked. without recognizing themselves. and the commoners will be delighted with the mockery they understand. The actors will not move about on stage. The blocking is stagnant with the actors reciting their literary and crafted lines, creating the drama or amusement with inflection and expression. If the play is a sentimental one, it will have been written by Marivaux, who excelled at the game of love and hate, crafting lines that would compliment a woman just so, and induce jealousy. If it is tragic the playwright will be Voltaire, who wrote 53 plays, more than half of them tragic. Voltaire dominated French tragedy, just as he virtually dominated all of French thought and literature, just as his face--the large grey and black image suspended

on the right--dominates this panel as salute to the masters of French Classic Theater.

Voltaire (Francoise -Marie Arouet) 1694-1778

Moliere--1622-1673

Marivaux--1688-1763

Victor Hugo – 1802-1885

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare, 1564-1616, English, playwright of 38 plays, actor, and shareholder in

acting troupes and theater buildings, was not the darling of his time. His fame began to grow

in the late 17th century and peaked in the 19th century, immortalizing him as the finest playwright

in the history of theater. Why? In the millions of words that have been written and used to explain

and explore the brilliance of his work, the simple truth stands that these plays remain the plays

by which all others are judged. Infinitely performed, studied, read, they stand alone – unparalleled.

Is it the characters--well rounded, sometimes tragic, sometimes absurdly comic, always human, never stereotypes? Or is it his penetrating insights into human behavior? Perhaps it is the sheer entertainment

of a perfectly scripted tale or the illuminating dialog that transcends the script, showering the audience

with associations and connotations that reach far beyond the tale of love, sorrow, courage, failure

into their own world, their own drama. These symbolize Shakespeare as an entity unto himself, Zarka

has chosen to portray three of his most beloved and performed works: Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth,

and Hamlet. On the left side of the canvas, Romeo is climbing to his love, Juliet, who is waiting on the balcony. Center is the ghost of Hamlet¹s father, looming over the work setting the tone of tragedy echoed

in the darkened purple sky, the moving waters below.

Forefront and on the right is Hamlet eternally asking: “To be or not to be…”.

William Shakespeare – 1564-1616

Romeo and Juliet –1594-1595

Macbeth – 1605-1606

Hamlet – 1600-1601

acting troupes and theater buildings, was not the darling of his time. His fame began to grow

in the late 17th century and peaked in the 19th century, immortalizing him as the finest playwright

in the history of theater. Why? In the millions of words that have been written and used to explain

and explore the brilliance of his work, the simple truth stands that these plays remain the plays

by which all others are judged. Infinitely performed, studied, read, they stand alone – unparalleled.

Is it the characters--well rounded, sometimes tragic, sometimes absurdly comic, always human, never stereotypes? Or is it his penetrating insights into human behavior? Perhaps it is the sheer entertainment

of a perfectly scripted tale or the illuminating dialog that transcends the script, showering the audience

with associations and connotations that reach far beyond the tale of love, sorrow, courage, failure

into their own world, their own drama. These symbolize Shakespeare as an entity unto himself, Zarka

has chosen to portray three of his most beloved and performed works: Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth,

and Hamlet. On the left side of the canvas, Romeo is climbing to his love, Juliet, who is waiting on the balcony. Center is the ghost of Hamlet¹s father, looming over the work setting the tone of tragedy echoed

in the darkened purple sky, the moving waters below.

Forefront and on the right is Hamlet eternally asking: “To be or not to be…”.

William Shakespeare – 1564-1616

Romeo and Juliet –1594-1595

Macbeth – 1605-1606

Hamlet – 1600-1601

Russian Theater

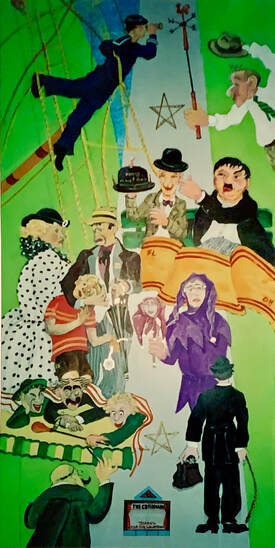

The Comedians

Laughter! Laughter brings us joy and escape; forces us to look at ourselves; raises questions,

solves mysteries, equalizes us as one mankind. While comedy was the last major dramatic form

to receive recognition in ancient Greece, not until 487-486 B.C., it was, nonetheless, already beloved

and remains so. It has been said that “dying is easy; comedy is hard”. The comedians portrayed

here make comedy look easy. Whether by means of slapstick, dry wit, satire or double entendre,

these masters of humor seized their audiences¹ hearts, made them laugh, made them

Forget, stood their world on its head, and did their job – they entertained.

From top to bottom we see Buster Keaton (1895-1966); Jimmy Durante (1893-1980);

Stan Laurel (1890-1965) and Oliver Hardy (1892-1957); W. C. Fields (1879-1946);

Mae West (1893-1980): Woody Allen (1935-); The Marx Brothers – Chico (1886-1961),

Harpo (1888-1961), and Groucho (1890-1977);

and finally The Little Tramp, Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977).

Laughter! Laughter brings us joy and escape; forces us to look at ourselves; raises questions,

solves mysteries, equalizes us as one mankind. While comedy was the last major dramatic form

to receive recognition in ancient Greece, not until 487-486 B.C., it was, nonetheless, already beloved

and remains so. It has been said that “dying is easy; comedy is hard”. The comedians portrayed

here make comedy look easy. Whether by means of slapstick, dry wit, satire or double entendre,

these masters of humor seized their audiences¹ hearts, made them laugh, made them

Forget, stood their world on its head, and did their job – they entertained.

From top to bottom we see Buster Keaton (1895-1966); Jimmy Durante (1893-1980);

Stan Laurel (1890-1965) and Oliver Hardy (1892-1957); W. C. Fields (1879-1946);

Mae West (1893-1980): Woody Allen (1935-); The Marx Brothers – Chico (1886-1961),

Harpo (1888-1961), and Groucho (1890-1977);

and finally The Little Tramp, Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977).

The Dancers

Dance! Breathtaking athletic grace set to music, timed with precision, choreographed with wonder.

Dance has been a part of theater as long as there has been theater. The combination of snappy songs,

easily understood plots, lavish scenery and show stopping dance sequences is irresistible and alluring.

1940-1968 is recognized as being the Golden Age of Musical Comedy. Before, during, and since, dancers have captivated us

with the beauty of the perfect kick and feline leap, the rush and rhythm of tapping feet and stunned us

with the perfectly timed stop, the breathless pause. Often in heels, usually smiling, always beyond our everyday existence

are the dancers of musical theatre. Represented here are some of the most renowned and convention

setting artists of their time, or any time, as salute to all of the conviction, talent, skill, and artistry that is part of theatre¹s

long history and appreciation of the body in motion.

From right to left: Frank Sinatra (1915-1998) in New York; Ann Miller¹s (1923--) tango; Gene Kelly

(1912-1996); Judy Garland (1922-1969); Tommy Tune, Bob Fosse (1927-1987), Fred Astaire

(1899-1987) and Ginger Rogers (1911-1995).

Dance has been a part of theater as long as there has been theater. The combination of snappy songs,

easily understood plots, lavish scenery and show stopping dance sequences is irresistible and alluring.

1940-1968 is recognized as being the Golden Age of Musical Comedy. Before, during, and since, dancers have captivated us

with the beauty of the perfect kick and feline leap, the rush and rhythm of tapping feet and stunned us

with the perfectly timed stop, the breathless pause. Often in heels, usually smiling, always beyond our everyday existence

are the dancers of musical theatre. Represented here are some of the most renowned and convention

setting artists of their time, or any time, as salute to all of the conviction, talent, skill, and artistry that is part of theatre¹s

long history and appreciation of the body in motion.

From right to left: Frank Sinatra (1915-1998) in New York; Ann Miller¹s (1923--) tango; Gene Kelly

(1912-1996); Judy Garland (1922-1969); Tommy Tune, Bob Fosse (1927-1987), Fred Astaire

(1899-1987) and Ginger Rogers (1911-1995).

Modern American Theater

Exploring the depths of the human condition is what American dramatists do best. In this relatively new country,

we are at odds with ourselves. Playwrights of the modern era return to this theme again and again exploring our sense of anguish

at the absurdity of our plight and the concept of The American Dream--is it a possibility, and at what cost? Can we have it all,

be it all, live the picturesque lives of our advertising? And if so, who suffers the price, where becomes of our humanity?

Our authors ask questions and they occasionally suggest answers, although often only partial ones. They reach into the

human psyche to examine morality and sexuality and the roles they play in relationships and society at large.

How do our actions touch others? How far can we bend the rules? Zarka has chosen a selection of America¹s finest and

most beloved to represent this period, with scenes that are now a part of our cultural identity and a tapestry

of what we as Americans often think of when we think of theater.

From left to right: Tennessee William¹s A Streetcar Named Desire, Arthur Miller¹s A View From The Bridge,

Death of A Salesman, The Crucible, Samuel Beckett¹s Endgame.

(While Beckett is not American, he was included in this collection as his work is similar in theme and time period.)

Tennessee Williams – 1911-1983; A Streetcar Named Desire – 1947.

Arthur Miller – 1916--; A View From The Bridge -1955;

Death of A Salesman – 1949; Crucible – 1953.

Samuel Beckett – 1906-1989; Endgame – 1957.

we are at odds with ourselves. Playwrights of the modern era return to this theme again and again exploring our sense of anguish

at the absurdity of our plight and the concept of The American Dream--is it a possibility, and at what cost? Can we have it all,

be it all, live the picturesque lives of our advertising? And if so, who suffers the price, where becomes of our humanity?

Our authors ask questions and they occasionally suggest answers, although often only partial ones. They reach into the

human psyche to examine morality and sexuality and the roles they play in relationships and society at large.

How do our actions touch others? How far can we bend the rules? Zarka has chosen a selection of America¹s finest and

most beloved to represent this period, with scenes that are now a part of our cultural identity and a tapestry

of what we as Americans often think of when we think of theater.

From left to right: Tennessee William¹s A Streetcar Named Desire, Arthur Miller¹s A View From The Bridge,

Death of A Salesman, The Crucible, Samuel Beckett¹s Endgame.

(While Beckett is not American, he was included in this collection as his work is similar in theme and time period.)

Tennessee Williams – 1911-1983; A Streetcar Named Desire – 1947.

Arthur Miller – 1916--; A View From The Bridge -1955;

Death of A Salesman – 1949; Crucible – 1953.

Samuel Beckett – 1906-1989; Endgame – 1957.

The Musicals

The dazzle, magic and splendor that is theater is more evident in the musical than any other form. Packaged together are music, dance, song, lights, plot, costumes and scenery that suspend belief, heighten the senses and create a fantasy world unlike anything the everyday can suggest. We do not go to musicals for reality, although certainly realistic themes play their part. We go to musicals for wonder and enchantment. The last few decades have brought us a bonanza of box office breaking spectacles that are so well known that theater goers and nontheater goers alike recognize their images and hum their tunes. Perhaps it is the advent of television, video, and the thousands of films that are produced each year that has created a rich market for the musical. We have become an audience saturated with words and pictures and stories, yet we are always on a quest for more. Unlike a drama that can be recreated to a certain--although different--degree on film, the musical stands alone as primarily a stage experience. Audiences demand an event. With the modern musical, they are given one. Originally believed to primarily be an American theater form, the most popular and loved musicals of the last 20 years have been written by Andrew Lloyd-Webber, an Englishman, and the French team of Alain Boubil and Claude-Michel Schonberg proving that while Americans may have perfected the form, it is loved by the whole of the world. From left to right: The Phantom of the Opera (by Andrew Lloyd-Webber), Cabaret (by John Kander), The Wizard of Oz , Amadeus (by Peter Schaffer, 1980), Les Miserables (by Alain Boubil and Claude-Michel Schonberg, 1985), Cats (by Andrew Lloyd-Webber, 1981), Fiddler on the Roof (by Joseph Stein, Jerry Bock, and Sheldon Harnick), Miss Saigon (by Alain Boubil and

Claude-Michel Schonberg).

Claude-Michel Schonberg).